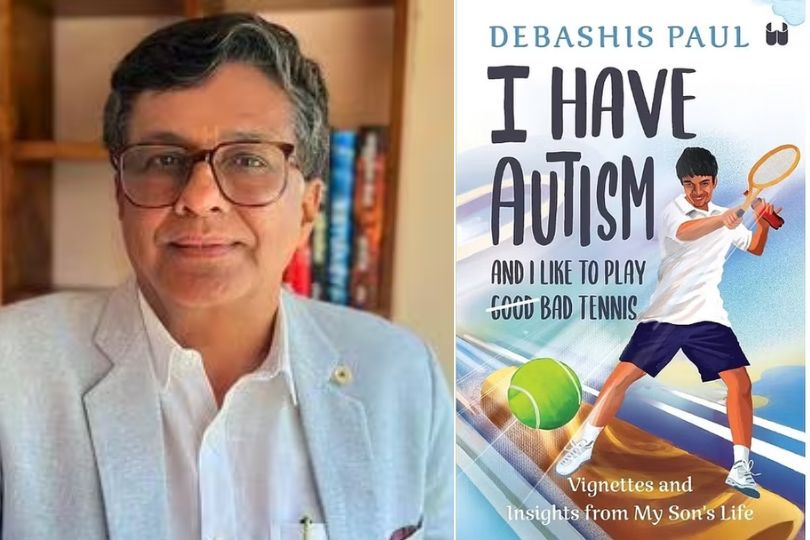

Interview with Debashish Paul, Author of “I Have Autism And I Like To Play Bad Tennis”

Explore the inspiring journey of Debashish Paul, author of 'I Have Autism And I Like To Play Bad Tennis,' in a compelling interview on Frontliston Nov 15, 2023

Frontlist: Your book emphasizes that children with autism may struggle to form emotional and empathetic connections with friends. Can you share your perspective on this aspect, including its implications for these children and their social development? Furthermore, in your view, how can society take steps to offer improved support and understanding for individuals with autism in the context of these social and emotional challenges?

Debashish: In most children and adults with the condition of autism, the social dimension is impaired. The degree of difficulty would vary from case to case. Generally speaking, they would be different from the neurotypically developing children in social communication, learning, and forming relationships and emotional connections. Now, if you reflect on the social facets of our everyday life, you will see that everything has a social component. Going to a school is a social act, learning from a teacher entails certain social exchanges, and any celebration is a social event. So aside from several other deficit areas that need remedial interventions like motor coordination, language learning, speech, levels of anxiety arising from break-in routines, etc., one could conclude that the 'social' becomes the overarching disability.

But the good news is that there are methods/ techniques to improve social comprehension, social compatibility, and behavior. But this calls for parents, caregivers, special educators, and therapists to possess the necessary skills, consistency, patience, hard work, and resilience.

For a secure life, a healthy life, productive engagements, and a pervasive sense of well-being, society has a large role. School administrations, employers at large, and public establishments, first and foremost, must become fully aware of this condition. The significant hurdle, even in this age of the internet, is the lack of awareness and the resultant indifference, discrimination, and the absence of empathy on the part of society.

So, the first step would be to acquire basic knowledge of the condition. Then, orient oneself, the immediate community, the neighborhood, and the organization to widen the attitude of acceptance and understanding. Then, move up to create opportunities for the child (or adult) to blossom, uncover the talents, provide support, and find solutions to make it easier for the parents and the person with autism.

This can come about when the belief is framed that neurodivergent people can contribute very productively and creatively in work processes.

The leadership must dissipate the prevalence of the surrounding prejudices in work cultures and organizations.

Parents have a major role, and they need courage in every step to hold up against societal negativities and use their influence and persuasion. They need the strength to crawl out from the caverns of hopelessness. They need help to cut through the bars of the cage of prejudices. They need emotional support and direction. They need hope from the extended family and society all the way.

Frontlist: Your book, "I Have Autism," portrays the strong bond between Noel and his sister, highlighting their love for each other. Can you share insights into how their bond became so deep and special, also were there any challenges in the process?

Debashish: Let me draw a bit from my book (Chapter 1- I Know I Am Different).

Our daughter Ahvana, Noel's "Bonu", 4 years younger than him, grew up to be a wonderful, bossy little sister who was deeply protective of Noel. Even so, they had their usual sibling rivalries right through -squabbling over belongings and space, the harmless jostle for attention, and fighting over the relative share of importance.

Whenever Noel found Ahvana having a long, excited conversation with her mother or with me after an outing or at the end of the day, on return from school, he would interject with mild irritation. 'Bonu, don't say the same thing again and again.' This was an oft-used taunt to tick off his sister. It was possibly rooted in his feeling of being sidelined in a particular situation for too long. He wanted some of the attention of the people around - more so if it was his mum or dad.

When Ahvana started to go to school (Noel was in the Special Ed section of the same school), she began to understand the social challenges that Noel faced. Noel was also bullied at times by boys his age. She used to cry a lot; constant explanations and guidance by me and her mum were needed to safeguard her from a sense of victimhood – "The world is such an unjust place" was her constant refrain when she was 7 -8 years old. We had to be constantly pushing up her resilience. She learned from her parents how to be protective and caring about him, making small everyday sacrifices for him. She read about autism, for which I gave her some kid-friendly illustrated material that she promptly pinned on her study table soft board and started to respect him for the person that he was truly.

I used to notice that Noel missed her a lot when she was away for a school trip or later when she traveled on holidays abroad. Noel used to give a running commentary of what she must be doing, the places she must be visiting, what new cuisines she must be enjoying, and so on. A warm bonding encased in innocence and pure love fostered year after year. Ahvana became a young lady and joined the University but always had time for her brother and included him in her outings with her close friends. They were all so warmly accepting of Noel and his quirks, his social goofs.

Frontlist: In your book, you express a unique perspective on preparing Noel for work at an early age, which differs from the typical focus on making children feel safe and worrying about their future. Can you share your thoughts and preparations regarding this approach? How did you handle the potential questions and concerns of the society?

Debashish: It took years to get into the mode of whole-hearted acceptance. My worldview had to change, requiring a lot of work. The recalibration of what constitutes success and happiness was the big one. To step aside from the adrenaline rush of the proverbial 'rat race' was one such important dimension. That would not have happened if I remained in the usual ambition track.

I had to find time to apply myself in the area of seeking workplace opportunities for Noel's learning of elementary work skills side-by-side with the social adjustments that are necessary in a work environment.

Noel was introduced to elementary kitchen skills at home – and he could chop and grate veggies and make sandwiches and brownies independently from the age of 12. After school hours, Noel (then 16) joined a bakery that also had an adjacent retail unit. This was necessary, I thought, to understand the concepts of work life, workplace, and remuneration in exchange for work. Unless these are explained in simple ways and reinforced, I felt he wouldn't be ready when he leaves school (the impending school exit at 18 was looming large). All this was because it was clear that Noel would not be able to take on academics in any form at a higher level.

Dealing with the concerns and insinuations of people around me was easy as I had absolutely no baggage about social class appropriateness of jobs. I respected every job and everyone at the workplace. That was a key part in the shaping of my worldview.

I was genuinely free-spirited here. I had done my recalibrations and priority settings rather early in my parental journey and had let go of the urge to achieve my goals through my kid vicariously.

I only laughed at the comments of the people and their discouragement.

I was rock-solid in my resolve to make this happen for Noel.

Frontlist: We all fell in love with Noel and his innocence while reading your book. Is there one thing you learned from him during your journey as a parent that truly amazed you and left a lasting impact on you?

Debashish: Well, when you step into the autism landscape, you are faced with a surfeit of lateral ideas and expressions. My book is full of them! It is bound to fill you with surprises and sure to make you chuckle when you read the goofy scenarios drawn from everyday life. The title of my book is a merger of my son Noel's actual statements that he often used. The 'like to play bad' tennis is a noteworthy comment – it represents his pushback to the hard, entrenched norms that we grow up with that we should 'play good, become good' at the sports we choose. So that we can compete and get ahead of others in the sports field. Noel believed that playing tennis should be all about enjoying the beautiful game. 'Bad tennis' became his short code for wholly enjoying the game with no concerns of how good you are at it. The book is full of such pushbacks to our one-track success and happiness definitions that we are all stuck with.

That in my book is lesson one.

Second, the mental strength to overcome adversity in life, the acceptance, and finding the fuel to reinvent oneself for the sake of another is something that one has to work on. Counselling helps but its the individual who has the power to transform himself/herself.

Finally, the discovery that the power of love is the most empowering and enduring force in many a situation. It will help you to overcome very difficult situations. That love can exist in all its intensity, in pain, humiliation, grief, respect, compassion, and companionship.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.